start > cultuursite > Strijd voor rechtvaardigheid > Strijd over visrechten Deatnu/Tana rivier

Strijd over visrechten Deatnu/Tana rivier

work in progress

1. Inleiding

In 2017 werd een nieuwe verdrag gesloten tussen Noorwegen en Finland over de visrechten in de Deatnu rivier. Deze rivier staat bekend als een van de beste zalmrivieren van Europa. De Daetnu vallei wordt al duizenden jaren bevolkt door de Samen. De visserij en met name de zalm is voor deze gemeenschap een essentieel deel van hun cultuur.

Achtergrond van het verdrag is de afname van de zalmpopulatie in de rivier.

Dit verdrag zou wel eens de doodsteek kunnen betekenen voor de Samische gemeenschap aldaar. De schrijver Aslak/Áslat Holmberg deed, vlak voordat het verdrag door de parlementen vastgesteld zou worden, via you-tube een emotionele en dringende oproep om af te zien van dit verdrag. Het mocht niet baten. Het verdrag werd aangenomen.

De video van 11 maart 2017 heeft als titel Indigenous salmon-fishing Saami criminalised by Finland and Norway. De video duurt 22 minuten en is gespoken en ondertiteld in het Engels.

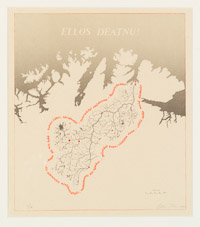

In de video kondigt Aslak Holmberg aan dat hij en andere Samen zich zullen gaan verzetten tegen dit verdrag. De actiegroep Ellos Deatnu! [Lang leve de Deatnu!] werd opgericht. De slogan verwijst met een knipoog naar de slogan van de strijd in de jaren zeventig tegen de bouw van een stuwdam in Altarivier: Ellos eatnu (Laat de rivier leven/ laat de rivier stromen). De actiegroep bestaat uit lokale Samen en andere activisten

In dit artikel ga ik in op de achtergronden van het verdrag en de acties die daarna zijn ondernomen. Dit zijn o.a.

het uitlokken van een proefproces.

het instellen van een moratorium waarin de actievoerders het verdrag voor een deel van de rivier opschorten.

1.1. De Deatnu rivier

De Deatnu (noors:Tana, Fins:Teno) is een 360-kilometer lange rivier in het Noordelijke deel van Samenland. Deatnu betekent "Grote rivier". De Deatnu mondt uit in Barentszee

De bovenloop vande Deatnu bestaat uit de zijrivieren Inari-rivier/Anarjohka en de Karasjohka/Karasjok-rivier.

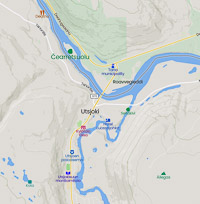

De rivier vormt de grens tussen Noorwegen (gemeentes Karasjok en Tana) en Finland (gemeentes Utsjoki en Inari).

2. Het verdrag van 2017

Sinds 1873 wordt de zalmvisserij al gereguleerd. Aan de Noorse kant is het vissen met netten alleen voorbehouden aan de inwoners van de riviervallei (overwegend Samen) die daar ook landbouw bedreven. Aan de Finse kant zijn de visrechten gekoppeld aan het eigendom van het aan de rivier liggende land.1

In 2017 sloten Noorwegen en Finland een nieuwe overeenkomst over de zalm vissserij in de Deatnu rivier. Doel van de overeenkomst was de bescherming van zalmpopulatie in de rivier.

Deze overeenkomst komt op het volgende neer 2:

Visquota voor het van vangen zalm met netten worden met 80% gereduceerd. De quota voor vergunningen aan toeristen worden met 40% gekort. Deze nieuwe quota raken de Samen dus het hardst

De visrechten van inwoners van de vallei die die daar niet permanent wonen, worden verder beperkt. Lokale bewoners die minder dan zeven maanden per jaar in de riviervallei wonen, komen niet meer in aanmerking voor het aanvragen van visvergunningen als ingezetenen. De beperking wordt als bijzonder schadelijk beschouwd voor de lokale Samen-jongeren, zijn verhuisd om in Zuid-Finland te gaan studeren. Daarom wordt de overeenkomst gezien als een bedreiging voor het doorgeven van de visserijkennis en -vaardigheden van de Samen aan nieuwe generaties. Na de wijziging moeten lokale bewoners die voornamelijk elders wonen een visvergunning voor niet-ingezetenen kopen (bekend als de toeristische visvergunning)

Holmberg signaleert in een interview 3 dat er maar één groep is die er daadwerkelijk op vooruitgaat:

Wat de woede van lokale Samen verder vergrootte is de praktijk van niet-lokale huisjeseigenaren - meest Finnen uit het Zuiden - om hun visrechten te verhuren aan andere vissers.

De huteigenaren op hun beurt zijn ook woedend: "We hebben ons eigendom legaal gekocht en het perceel was inclusief visrechten. Als we deze rechten niet kunnen gebruiken, is dat een duidelijke inbreuk op onze fundamentele eigendomsrechten.”4

De Samen beschouwen de overeenkomst in strijd met de constitutionele rechten van de Samen en in strijd met internationale afspraken over de rechten van inheemse vollken. Daar komt bij dat ze nauwelijks betrokken zijn geweest bij de opstelling van de overeenkomst. Ook dit is in strijd met het internationale recht.

3. Rechtszaak Veahčak & Ohcejohka visrechten

In de zomer van 2017 gingen drie Samische vrouwen zonder vergunning vissen in Veahčak/Vetsikko een zijrivier van de Deatnu in de gemeente Ohcejohka/Utsjoki. Zij meldden zich daarna bij de politie wegens overtreding van de visserijwet. Een andere Same deed min of meer hetzelfde. Hij had wel een vergunning maar ging vissen in de Ohcejohka/Utsjokierivier met een volgens de wet verboden vistuig. Zo lokten ze een proefproces uit.

Alle vier de beschuldigde vissers zijn lokale Sámi, wiens families al eeuwenlang castlinen en andere visserijactiviteiten uitoefenen in de wateren van het Deatnu-riviersysteem. Het vissen op zalm in dit riviersysteem is een essentieel onderdeel van de Sámi-cultuur die werd en nog steeds wordt gedaan voor levensonderhoud, economische ontwikkeling en spirituele en identiteitsdoeleinden.

Tot de zomer van 2016 waren de Sámi in de Deatnu vallei vrij om hun aloude en cultureel vitale tradities uit te oefenen en hadden ook specifiek het recht om vrij te vissen. De nieuwe wet veranderde dit - zoals hierboven al toegelicht. Vanaf nu mag er alleen met een vergunning worden gevist. De lokale Sámi-bevolking wordt nu gedwongen te betalen voor het recht om hun cultuur te beoefenen in wateren die door de Finse staat tot haar eigendom wordt gerekend.

Het recht om vrij te vissen is voor de Samen een belangrijk middel om traditionele kennis en methoden levend en bloeiend te houden. Zij beroepen zich op het VN verdrag dat stelde dat de Samen het recht hebben om in hun traditionele levensonderhoud te voorzien (ook met meer moderne vistechnieken).

In maart 2019 concludeerde de rechtbank dat de Samen in hun recht stonden. Het Zweedse Arjeplognytt kopte: "The court has now declared that we Sámi have rights to our culture".

De rechtbank stelt dat de inperking van grondrechten gebaseerd moet zijn op aanvaardbare criteria. In dit geval zijn er geen aanvaardbare redenen gevonden om de grondrechten in te perken, aldus de rechtbank.

In haar arrest geeft de rechtbank toe dat de traditionele visserij van de Sámi geen bedreiging vormt voor de zalmpopulaties in de rivieren Vetsikko en Utsjoki. Daarom is het niet nodig om deze traditionele visserij te beperken, zoals in de nieuwe regelgeving.

De Finse staat ging in hoger beroep. In april 2022 oordeelde de Finse Hoge Raad dat de vissers in hun recht stonden. De Samen is praktisch het recht ontzegd om op zalm te vissen in hun eigen rivier, en dat is in strijd met een grondrecht dat voor de Samen in de grondwet wordt beschermd, aldus het hof.

Echter, de uitvoering van de uitspraak van het hof laat nog op zich wachten. Het ministerie van van Landbouw en Bosbouw stelde voor de zomers 2021 en 2022 een totaal visverbod in voor de Deatnu. 5

Scott Thornton en Kati Eriksen maakten een film over deze zaak: Home River. Hieronder ziet u een ruwe montage van deze film. De film duurt 16 minuten. Het geeft een goed beeld van de motieven van de drie Samische vrouwen: "the day that we lose our connection to the land and waters, we are no longer indigenous people".

Zie ook de website Home River

De Canadese website Eye on the Arctic gaf het volgende commentaar op de uitspraak.

De aanklachten hadden betrekking op het recht van de Samen om in de Tenojoki-rivier in Utsjoki en Vetsijoki zonder visvergunning te mogen vissen.

In de zaak in Utsjoki eiste de aanklager dat een lokale Samische visser werd bestraft voor het overtreden van visregels. De man had in augustus 2017 met een statisch net zalm gevangen buiten het officiële visseizoen. De rechtbank oordeelde dat de regelgeving over seizoensgebonden visserij in strijd is met de grondwettelijke rechten van de Samen en verwierp de aanklacht.

In de zaak Vetsijoki eiste de aanklager dat vier lokale Samen moeten worden veroordeeld voor vissen zonder vergunning. Zij hadden zonder toestemming van de Finse bosbeheerorganisatie Metsähallitus met een hengel en kunstaas gevist in de rivier. De rechtbank oordeelde de eis van een aparte vergunning de rechten van de Samen onterecht beperkten. Ook deze aanklachten werden verworpen.

De uitspraken, die woensdag werden bekendgemaakt, sloten aan bij eerdere vonnissen van de districtsrechtbank van Lapland. De aanklager had de eerdere vrijspraken aangevochten om een principiële uitspraak van de hoogste administratieve rechtbank te verkrijgen.

De oorspronkelijke uitspraak stelde dat de Samen een grondwettelijk gegarandeerd recht hebben om in hun 'thuisrivieren' te vissen en dat beperkingen op dat recht in strijd zijn met Finland’s verplichtingen onder internationale mensenrechtenverdragen.

De districtsrechtbank oordeelde ook dat de rechten van de Samen werden ondermijnd door de verkoop van visvergunningen aan toeristen, terwijl de Samen zelf op dat moment hun visrechten opeisten.

4. Ellos Deatnu! - het moratorium

In 2012 startte de de actiegroep Ellos Deatnu! een actie waarin ze besluiten een moratorium op te leggen

[..]

In een video worden de motieven voor het moratorium uitgelegd. De video heet Duhát Jagi - For Thousand Years, stamt uit 2022 en is gesproken Noord Samisch met Engelse ondertiteling.

Op de website Ellos Deatnu wordt het moratorium uitgelegd 6. Ik vat de tekst is het kort samen:

Er is een moratorium afgekondigd voor het eiland Čearretsuolu met betrekking tot de nieuwe visserijvoorschriften voor de rivier Deatnu (Tana/Teno). Dat eiland ligt nabij Utsjoki. Het Moratorium houdt in dat de uitvoering van de nieuwe visserijregels wordt stopgezet.

Deze voorschriften bedreigen het welzijn van de Samen die in de Deatnu-vallei wonen en werken.

Het vissen op zalm speelt een onmisbare rol in de manier van leven van de Samen. De nieuwe regels vormen een duidelijke schending van de mensenrechten en de rechten van inheemse volkeren, evenals van de grondwetten van Noorwegen en Finland. Over de nieuwe regelgeving is onderhandeld tussen de staten Noorwegen en Finland. De inbreng van de lokale Samische gemeenschap was verwaarloosbaar.

Vissen in het Moratorium-gebied mag op geen enkele manier de visserijrechten of -belangen van Saami belemmeren. Deze rechten zijn stevig verankerd in de verdragen, verklaringen en aanbevelingen van het internationaal recht. Ze worden ook ondersteund door de Noorse en Finse staatsgrondwetten, Samische ideeën over rechtvaardigheid en het Samische gewoonterecht.

Dit moratorium is van kracht totdat er over nieuwe regels voor de visserij in de Deatnu is onderhandeld. Deze onderhandeling moet op een correcte en eerlijke manier worden gedaan en gebaseerd zijn op Free, Prior and Informed Consent 7. Alle discussies moeten worden geleid door lokale Samen.

Tijdens het moratorium in deze regio zullen Samische ideeën over rechtvaardigheid en het Samische gewoonterecht worden toegepast.

Aangezien de nieuw opgelegde regels zijn stopgezet, zijn alle toeristische visvergunningen die niet lokaal zijn goedgekeurd, niet van kracht in deze regio. Toeristen die willen vissen moeten daarom toestemming vragen aan de Samische bevolking van de Deatnu-vallei, en vooral aan de familie wiens traditionele gebied dit is, d.w.z. de Helándirs.

4.1. Moratorium Office

Op het eilandje Čearretsuolu is een kunstzinnig project gestart van de artiest Outi Pieski, de artiest en activiste Jenni Laiti, de dichter en muzikant Niillas Holmberg getiteld Moratorium Office. Het doel van het project: "Het Moratoriumkantoor is een combinatie van kunst en activisme (artivisme) en biedt iedereen hulpmiddelen en informatie om hun eigen dekoloniale moratoriums uit te roepen. Dekolonisatie betekent het ontmantelen van buitenlandse macht en het teruggeven van de macht aan de inwoners van het gekoloniseerde gebied. Het doel van het project is mensen te versterken en te activeren om in actie te komen voor gemeenschappelijke doelen." Zie verder de website van de dichter Niilas Holmberg met daarin een krachtige tekst Time Out, Moratorium In! 8 Enkele fragmenten uit deze tekst:

Als reactie hierop kwam een groep kunstenaars die-geen-tijd-te-verliezen-heeft, samen met een stel genoeg-is-genoeg activisten, met een time-out gebaar: een moratorium.

[...]

Met het besef van klimaatverandering wordt inheemse zelfbeschikking wereldwijd als een noodzaak beschouwd. Toch lijkt het, ondanks de milieuproblematiek, onwaarschijnlijk dat inheemse naties soevereiniteit zullen krijgen.

Het is levensgevaarlijk om iemand die daar moreel geen recht op heeft om toestemming te moeten vragen om te mogen bestaan. Het is aan ons om te stoppen met vragen om het onbereikbare en zelf in actie te komen.

Tot zover het moratorium.

Leden van het Centre for Environmental and Minority Policy Studies verklaarde zich solidair met het moratorium. Op hun website cemipos doen ze er verslag van.

5. De stand van de zalmpopulatie 2022

Sinds 2017 is de zalmpopulatie verder gekrompen. De Finse staat heeft voor de zomers 2021, 2022 en vermoedelijk ook 2023 een algeheel visverbod ingesteld.

In een interview van april 2022 met het magazine The Circle van het Wereld Natuur Fonds (WWF) spreekt Aslak Holmberg zijn zorgen uit.

Het is onduidelijk wat de achteruitgang veroorzaakt. Het is waarschijnlijk dat klimaatverandering hier een belangrijke rol speelt. Sommige vissoorten waar zalm van leeft, zijn mogelijk door de opwarming van het water verder naar het noorden gemigreerd . Aan de Finse kant van Sápmi is de gemiddelde temperatuur in de afgelopen één à twee eeuwen met meer dan 2°C gestegen. Het is ook mogelijk dat de zalm niet genoeg voedsel kan vinden en daarom niet in dezelfde aantallen terugkeert.

Wat echter interessant is, is dat het aantal jonge zalmen in de rivier niet zo sterk is afgenomen als het aantal terugkerende volwassen zalmen. Dat vertelt ons dat ze simpelweg niet terugkomen. Atlantische zalm keert bijna altijd terug naar de rivier waar hij zich voortplant. Waarschijnlijk overleven ze dus hun trektochten door de oceaan niet. We weten niet waarom.

Zelfs onze traditionele kennis helpt ons niet echt om de kern van het probleem te begrijpen. Dat komt omdat de grootste veranderingen in de oceaan plaatsvinden, niet in het zoete water—en de oceaan is een uiterst complex ecosysteem. Natuurlijk kunnen we nog steeds beheersmaatregelen voorstellen, zoals quota op de vangst van vissoorten waar zalm van leeft of strengere regels voor de zalmkweekindustrie, die de grootste bedreiging vormt voor wilde zalm. Inheemse kennis vertelt ons ook dat een verhoogde visserij en jacht op zalmroofdieren zou helpen. Maar verder komt het neer op het beperken van de gevolgen van klimaatverandering.

Daar komt nog bij dat we nu ook te maken hebben met een invasieve soort. Roze zalm (ook bekend als Pacifische of humpback-zalm) heeft de rivier zo goed als overgenomen—vorige zomer waren er vier keer zoveel roze als Atlantische zalmen. Dit verandert de aard en samenstelling van de rivier, inclusief de voedingsstoffen, omdat roze zalm sterft na het paaien. Er wordt geschat dat er volgende zomer wel een half miljoen van hen in de rivier kunnen zitten.

Als iemand die afhankelijk is van zalm en zich persoonlijk verbonden voelt met de oceaan, baart de toekomst me grote zorgen.

6. Deatnu - grensrivier

Aansluitend op de Kafkaeske toestanden uit hst 4 nog het volgende.

De Deatnu vormt voor een groot deel de grens tussen Noorwegen en Finland.

De wet verbiedt het om samen te vissen als de ene uit Finland en de andere uit Noorwegen komt

Aslak Holmberg, die aan de Finse kant van de rivier woont, legt dit uit:

Ik geloof dat er momenteel een rechtszaak loopt waarbij twee mannen samen in dezelfde boot aan het drijfnetvissen waren, een methode die twee mensen vereist omdat je het niet alleen kunt doen. In dit geval was de ene man van de Finse kant en de andere van de Noorse kant. Ze werden betrapt, beboet en zijn vervolgens naar de rechter gestapt.

Ook werd het illegaal voor ons om op de Noorse kant cloudberries (bergframbozen) te plukken en ze vervolgens mee terug over de grens te nemen. Mijn familie komt van beide kanten van de grens. Mensen zijn er al generaties aan gewend om hun bessen of vis aan de andere kant te halen.

DeanuInstituhtta

DeanuInstituhtta is een kenniscentrum voor de zalmvisserij en de riviergebonden Samische cultuur van de regio. Het instituut doet onderzoek naar de traditionele kennis, met een specifieke focus op de Tana-rivier en het Tanafjord-gebied. Een ander belangrijk aandachtsgebied is de lokale kennis over rendierhouderij en traditionele vormen van levensonderhoud in de regio.

DeanuInstituhtta is een stichting van de lokale zalmvisserij- en rendierhouderijverenigingen. De organisatie wordt geleid door een raad van vijf personen. Het idee is dat het instituut projecten ontwikkelt in samenwerking met relevante instellingen ten behoeve van de regio en haar inwoners. Op lokaal niveau gebeurt dit via het Joddu-project van de gemeente Deanu, en op nationaal niveau werkt het samen met het Wild Salmon Center in Noorwegen.

Zie verder: website DeanuInstituhtta. Deze website bevat interessante artikelen (in het Noors en Samisch).

© 2022, aangepast maart 2025

Overzicht geraadpleegde literatuur en literatuur om verder te lezen.

Holmberg, Aslak (2018). Bivdit Luosa – To Ask for Salmon: Saami Traditional Knowledge on Salmon and the River Deatnu: In Research and Decision-making. *

Ook online.

Meer informatie...

Joks, Solveig & Law, John (2017). Sámi salmon, state salmon: TEK, technoscience and care. *.

Ook online.

Kuokkanen, Rauna (2020). The Deatnu Agreement: a contemporary wall of settler colonialism. *.

Ook online.

Meer informatie...

Vilpponen, Susanna (2019). Journalism and Colonialism in the Deatnu River Case: A study of Sámi viewpoints. *

Meer informatie...

Noten

Since 1873, salmon fishing in the Deatnu River has been regulated by bilateral agreements negotiated between Norway and Finland. For the local Sámi, the agreements have signified a gradual external control of fishing rights and erosion of traditional harvesting. For example, the first agreement in 1873 marked the prohibition of the fishing practices of goldin, duhásteapmi and rastábuođđu.*

These bans, however, were ignored to a degree for several decades, demonstrating the dominance and perseverance of Sámi law and norms in the region at least up until the mid-twentieth century. Each Deatnu agreement has introduced new restrictions on fishing gear, methods and the length of the fishing season.

* In duhásteapmi, a torch is employed to lure the fish which is then caught with a spear.

Rastábuođđu is a weir across the river, a collective fishing method sometimes involving several villages. Goldin involves a weir across the river combined with driftnets and seines (zie ook de masterscriptie van Holmberg, 2018)

Rauna Kuokkanen (2020) The Deatnu Agreement: a contemporary wall of settler colonialism, p 509

Zie voor een meer uitgebreide beschrijving van de overeenkomst het artikel Rauna Kuokkanen (2020) The Deatnu Agreement: a contemporary wall of settler colonialism

Interview met Holmberg in Kuhn, Gabriel. Liberating Sapmi: Indigenous Resistance in Europe's Far North (p. 148). Pm Press.

Artikel Yle van juli 2016 Utsjoki residents at odds over Tenojoki salmon fishing restrictions: Summer home residents angry

Owners of holiday homes in the region have also added their voices to the opposition. Veikko Rintamäki is originally from Seinäjoki, but owns a second home on the banks of the Teno.

“We bought our property legally and the lot included fishing rights. If we can’t use these rights, it is a clear infringement of our fundamental property rights,” he said. He has submitted a complaint to the Chancellor of Justice that seasonal residents of the area were not sufficiently consulted in the preparation of the proposal.

Ook de toeristenindustrie was ontevreden. In hetzelfde artikel lezen we:

Tourism entrepreneur Heikki Tuovila has lived in nearby Yläköngäs all his life. He says one drift net captures more salmon that an entire village full of tourists.

“It is important that net fishing is limited because the size of the catches is so much larger than with angling. Angling has to be limited to some extent too because the Teno is overfished. But the permit quota system is too much,” Tuovila said.

He says the new quotas will threaten the tourism industry in the area, and adds that the majority of people with businesses catering to tourists in the area are also Sámi.

In een memo aan Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues van de VN (UNPFII) schrijft Aslak Holmberg:

However, [..] the implementation of the Ohcejohka rulings had an unfortunate start, as the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry did not take into account the key legal aspects of these rulings, and proposed to continue the total ban on salmon fishing in the river Deatnu for the upcoming summer.

Het betreft de 21e vergadering van de UNPFII

Tekst van de website Ellos Deatnu:

A Moratorium is declared in the area of Čearretsuolu island regarding the new fishing regulations for the Deatnu (Tana/Teno) river, as the new regulations threaten the wellbeing of the Saami from the Deatnu valley. Salmon fishing plays an indispensable part in the Saami way of life. The new regulations represent a clear violation of human and indigenous rights as well as of the constitutions of Norway and Finland, and these were negotiated with negligible consultation of the local Saami community. A Moratorium means that the implementation of the new fishing regulations is halted in the area surrounding Čearretsuolu. Čearretsuolu with its surrounding area is Saami territory.

Fishing in the Moratorium area may not in any way hamper Saami fishing rights or interests. These rights are firmly rooted in the conventions, declarations and recommendations of international law. They are also supported by Norwegian and Finnish state constitutions, Saami concepts of justice and Saami customary law.

This Moratorium is in force until new regulations are negotiated for fishing in the Deatnu. These new fishing regulations are to be negotiated in a proper and fair way using Free, Prior and Informed Consent, and all discussions are to be led by local Saami people. During the Moratorium in this region, Saami concepts of justice and Saami customary law will be applied.

Since the newly imposed regulations are halted, any tourist fishing licenses that are not locally approved will not be in force in this region. Tourist fishers must therefore ask permission from the Saami people of the Deatnu valley, and especially from the family whose traditional area this is, i.e. the Helándirs.

We encourage people in the Deatnu valley to declare a Moratorium in other areas along the Deatnu watershed as well until new fishing regulations have been negotiated and implemented.

Free, Prior and Informed Consent is een specifiek recht voor inheems volken en vastgelegd in de VN declaratie over de rechten van Inheemse volken.

Op de website van de VN organisatie FAO wordt het begrip verder uitgelegd.

Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) is a specific right that pertains to indigenous peoples and is recognised in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). It allows them to give or withhold consent to a project that may affect them or their territories. Once they have given their consent, they can withdraw it at any stage. Furthermore, FPIC enables them to negotiate the conditions under which the project will be designed, implemented, monitored and evaluated. This is also embedded within the universal right to self-determination.

Zie de website vam de FAO voor een verdere toelichting op bovenstaande.

De tekst op de website luidt als volgt:

Time Out, Moratorium In!

They are using time against us. The Nordic Governments – who claim ownership over the divided areas of Sápmi – are playing a trick of endless process and bureaucracy on us, the natives of Sápmi. How long are we supposed to scribble statements in committee meetings, which seem to exist in Kafkaesque nightmares? It would be inaccurate to say they are wasting our time because, ultimately, it’s them making us waste our time. We are wasting our time on a game that is theirs.

In response, a group of no-time-to-lose artists and a bunch of enough-is-enough activists came up with a time-out gesture: a moratorium.

A Moratorium is declared in the area of Čearretsuolu Island regarding the new fishing regulations for the Deatnu (Tana/Teno) River, as the new regulations threaten the wellbeing of the Sámi from the Deatnu Valley. Salmon fishing plays an indispensable part in the Sámi way of life. The new regulations represent a clear violation of human and Indigenous rights as well as of the constitutions of Norway and Finland, which were negotiated with negligible consultation of the local Sámi community.

A moratorium means that something is halted – for example, a law, action, or process. In this case, it means that the implementation of the new fishing regulations is halted in the area surrounding Čearretsuolu, which is Sámi territory.

That’s right, halted. Why play a foreign game of chess on water? Our pawns keep sinking whilst theirs come charging on pontoons. Why play anything on homeland with alien rules?

On this specified moratorium area, Finnish and Norwegian laws are no longer valid and Sámi concepts of justice and customary law have been applied. What are they going to do? Drag us away and lock us up? Fine us?

They haven’t. A year has passed and they haven’t even come and asked for a license to fish — the very idea that originally repulsed us and started this whole thing.

The support we got on local, national, and international levels has been nothing short of moving. A movement is often triggered by the experience of being touched and moved. We started getting messages from people expressing needs for moratoria of their own, in their home regions. Most of them seemed eager, and inspired to test this new way of securing their wellbeing. However, nearly all of them were concerned with the amount of effort it takes to establish a moratorium. So, how can we make the process as simple as possible?

Imagine if there was an advisory service you could approach with all kind of questions regarding any stages of setting up a moratorium. Imagine is there was an office which provides you with a moratorium kit containing guidance on how to proceed from A to Z; guidance for implementing a moratorium, clear instructions and templates for a moratorium declaration, press release etc. Well, behold The Moratorium Office.

We are living in a time in which Indigenous sovereignty on Indigenous lands is not only something that determines their futures as nations. In awareness of climate change, Indigenous self-determination is widely considered a global necessity. Yet in spite of environmental circumstances it seems unlikely that Indigenous nations will be granted sovereignty out of sheer good will, or even concern over our planet.

It’s deadly dangerous to ask someone morally unauthorized for a permission to exist. It’s on us to stop asking for the unobtainable and be proactive.

Meer informatie over de dichter Niilas Holmberg is te vinden op mijn website Noordse literatuur